Context

October 4, 2017

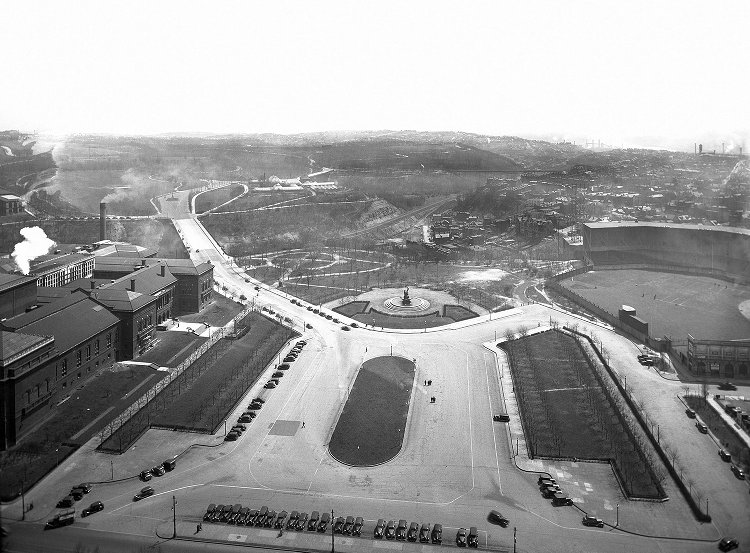

In the early twentieth-century the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Oakland, with its museums, park, and baseball field, was positioned as a cultural center and soothing escape from the grime of downtown. The dioramas were built at a time when the walls outside and inside of the museum were dark with soot. In this context, picturesque views of nature, space for leisure, and cultural activities worked together to offer an idealized vision of modern well-being.

Botany Hall was a conservation project, set up to try to encourage the preservation of increasingly vulnerable biomes. At the same time, money for the dioramas and other projects in the area came via philanthropy, and were thus funded by the very industries that were destroying the environment. Besides the direct sponsorship for the museum by Andrew Carnegie, the first dioramas of Botany Hall were supported by the women of Pittsburgh’s garden clubs, whose wealth could in many cases be tied to the burgeoning industries of the region.

In hindsight we can see that the cultural space of Oakland, and perhaps even the dioramas themselves, allowed the appreciation of nature to remain congruous with the glorification of industry. The diorama groups were conceived as opportunities for viewers to have an intimate encounter with a pristine version of nature, which would supposedly lead them to value the natural world more. However, while dioramas offer a powerful sensory experience, they do so in a way that keeps humanity and nature safely separated, visually suggesting a fundamental barrier between us and our environment.

Andrey Avinoff, Director of the Museum between 1926 and 1945 secured funding for the first dioramas in consultation with Rachel Hunt, whose wealth was derived from her husband Roy Hunt’s work with the Alcoa Foundation (Roy was also the son of Alfred E. Hunt, who founded the company). Alcoa produces aluminium, and is infamous for its contribution of airborne pollutants.

Even though Avinoff was known as an entomologist, he was also known as an artist, and it is clear that Botany Hall was of special interest to him. In the context of Avinoff’s interests and Hunt’s patronage, the representational strategies of the botanical dioramas, which must be described as picturesque and theatrical as much as scientifically accurate, come into clearer focus. It is important to imagine the museum, and the philanthropic culture that shaped the space of Oakland, as both driven by a dream of a unified sphere of progress and idealism of all kinds, rather than the division between art and science that came to structure the institutions in the later twentieth century.

Much of the history and context of Botany Hall can be gathered from its provenance. In archival terms, provenance refers to the information surrounding an object’s origin (creation), custody, and ownership. For a hall of dioramas, each with thousands of individual parts, provenance is difficult to establish. In the summer of 2016, two MLIS students set themselves to the task of determining the provenance of the Hall of Botany, conceived as a whole. Kate Madison and Emily Enterline conducted extensive provenance research as part of their Museum Archives class at the School of Computing and Information at the University of Pittsburgh. The following PDF presents the culmination of Madison and Enterline’s research, and concludes with the following provenance statement:

927 Andrey Avinoff [1884-1949] and Otto E. Jennings [1877-1964] and Garden Club of Allegheny County {1928 Penna. Spring Flora Group, 1929 Arizona Desert Group, 1931 Tropical Group, 1933 Mt. Rainer Group, 1934 Penna. Bog Group}; by 1940 (Works Progress Administration) and Frank A. Linder [unknown]; by 1942 Ottmar F. von Fuehrer [1896-1965] and Hanne von Fuehrer [unknown]; by 1973 Leroy K. Henry [1905-1983] and Dorothy E. Pearth [1914-1996]; {1965 Presque Isle Group, 1973 Penna. Hardwood Forest Group, 1976 Kitchen Herb Garden Group}.

Provenance Presentation – Botany Hall

This provenance research provides a clearer sense of the context within which the Hall was initially created and how it evolved, but also alludes to the complexity of documenting a collaborative, multi-year project such as this one. Dioramas pose a unique challenge in that they are not accessioned as part of the museum’s collection, but are also not considered a part of the archive. They exist in an unusual space because of their hybrid nature; they incorporate different degrees of human-made objects (from taxidermied animals to hand-molded wax leaves) presented in the form of a self-enclosed, miniature exhibition. How do they fit into the information ecosystem of the museum? This very question fueled our initial research. Dioramas are so often taken for granted, injested quickly and passively by viewers, if at all, yet offer numerous layers of interpretation in part because of their position in the history of museology.

Many natural history museums in the United States were established in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) was founded by Andrew Carnegie in 1896. Although the Smithsonian had been collecting artifacts and specimens of national interest since the mid 1800s, the National Museum of Natural History did not officially open its doors until March of 1910. Museum administrators at CMNH conducted an environmental scan of peer institutions in the late 1920s, valorizing the picturesque and naturalistic appearance of the animal displays at, for example, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.[1] In particular, the administrators were inspired by the plant habitat at the Field Museum, which illustrated “plant life in a most convincing and attractive manner.”[2]

Throughout the years, curators and artists from CMNH consulted collections at external institutions as part of their research for the botanical dioramas. Ottmar von Fuehrer, for example, studied the collections at the National Museum and the Field Museum of Natural History as part of his research about paleobotanical materials.[3] Still, the Hall of Botany is quite unusual in its arrangement and focus.

Louis Daguerre (1789-1851) and Charles-Marie Bouton (1781-1853) are credited with inventing the term “diorama” in 1822, prior to the foundation of most (if not all) of these American institutions of natural history. However, it is quite likely that dioramas of some shape and form existed prior to this time. Daguerre and Bouton utilized the diorama for theatrical purposes, combining translucent paintings with lively and evocative light shows to create a dynamic scene (see Getty Images).[4]

[1] Avinoff’s Memo to Dr. Clapp from the CMNH Library and Archives.

[2] Avinoff’s Memo, p. 2.

[3] Fortieth Annual Report of the Carnegie Museum, Carnegie Institute Pittsburgh, 1937.

[4] Tunnicliffe and Scheersoi, Natural History Dioramas, p. 7.