Environment

October 4, 2017Dioramas have long been associated with conservation efforts, as they were an early mechanism for conveying the magnificence of natural environments in an immersive way.

Round 1: The First Five Dioramas (1920s-1930s)

The Garden Club of Allegheny County was, historically, an organization motivated to conserve specimens that were approaching extinction (e.g.Trillium, Mountain Laurel, Orchids, Azalea, and Trailing Arbitus). As this Club was integral to the production of dioramas in Botany Hall, the conservation angle manifests throughout the Hall.

For example, between 1927-1928 members of the Garden Club attended the New York Show at Grand Central Palace. This display, they reported, was “staged in the interests of conservation, showed natural beauty and then desolation after the careless picnic party, camper or tripper had passed by. This made a deep impression…the decision was made to present to the Carnegie Museum a Habitat Group of the flora of Pennsylvania that will spell the lesson to every child who passes by and to ever thoughtful person who beholds it.” A note from the archives of the Garden Club of Allegheny at the University of Pittsburgh’s Archives Service Center states: “The reckless desecration of our native wild life is equally threatening to the realm of the local plants.” Please see this post, the 1920s Exhibit on Conservation, by Bonnie Isaac, to see a photograph.[1]

In May 1927, Church, Cogswell, DuPuy, Macfarlane and Avinoff wrote “to accept with thanks the kind offer of the Garden Club of Allegheny County to construct a botanical group which will emphasize the importance of conserving certain wild flowers in this vicinity which are rapidly becoming extinct.” In fact, the Garden Club of Allegheny County proposed a gift of $2,000 for a diorama they tentatively entitled “A Conservation of Local Plants Group.”[2] In 1928, the Pennsylvania Spring Flora or Laurel group was unveiled. An article in the Carnegie Magazine further stated that “this installation sounds a timely warning against the vandalism of the gentle sanctuaries of nature.”[3]

This group, also known as the Pennsylvania or Local Flora Group, is formally presented by Rachel Hunt, then President of the Garden Club of Allegheny County, to the public. The opening was well-attended, reportedly attracting over 150 members of the aforementioned club alongside guests of honor and Museum staff.

Press around the time of the opening of the new dioramas in the 1940s noted that the Garden Club of Allegheny County had also contributed to the improvement of the entrance to Schenley Park, which was visible from the windows that used to be in Botany Hall.

Round Two: The Final Three Dioramas (1960s-1970s)

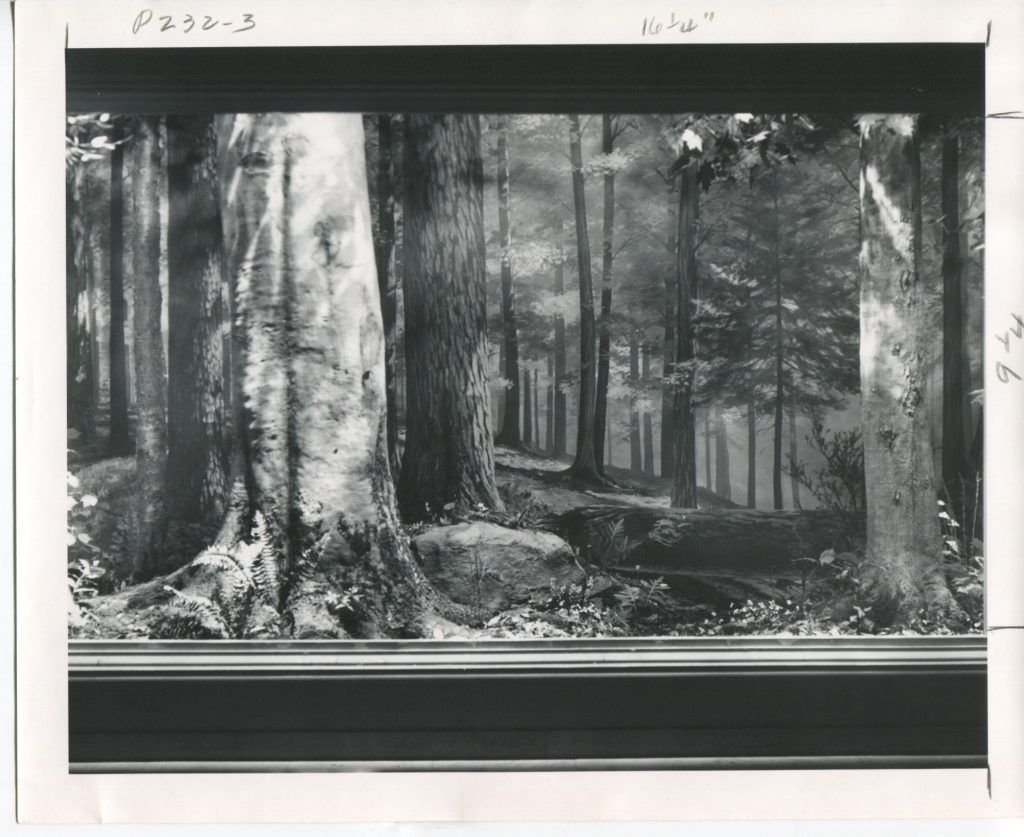

Dorothy L. Pearth describes the Hemlock-Northern Hardwood Forest display as representing an idyllic, virgin wood unmarred by humankind. In viewing the diorama, Pearth references the writing of the late Edwin L. Peterson (1915-1999), and specifically an excerpt from Penn’s Woods West, in order to express the importance of this work to reminding museum visitors of the importance and sanctity of the environment.

Peterson wrote: “Here in the quietness of the woods, we look at things more realistically, and we see how dependent we are on other forms of life- on the…squirrel who plants our trees, on the trees that preserve our water…”

From this, Pearth suggests that the diorama may bring the visitor to a quiet place and into the illusion of a tranquil wood. The small region replicated in the diorama represents “one of the few forested areas of any considerable size that has been neither disturbed nor destroyed by man’s activities.”[4] Through these descriptions, Pearth alludes to both the fragility of the environment and the necessity to acknowledge and even champion those sections of the natural world that persist despite and indeed completely separate from, humankind. This particular copse is hailed as “self-maintaining” and a region that “will not change drastically, barring catastrophe (such as interference by man) or a fundamental change in climate.” (231) Further, the site is in what Pearth called “the experimental portion of the Tract,” or a section that has “been set aside for preservation in its original condition.”

And we may remember too…that Pittsburgh, the biggest river port in the United States, ‘will be a greater port when the barges float on non corrosive water…and when watersheds are deeply forested.[4]

[1] Garden Club of Allegheny County files, Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh, 1928.

[2] CMNH Library and Archives,

[3] Article in Carnegie Magazine, 1928, p. 243.

[4] “Trees for Tranquility,” 1973, p. 231.