Process

October 4, 2017

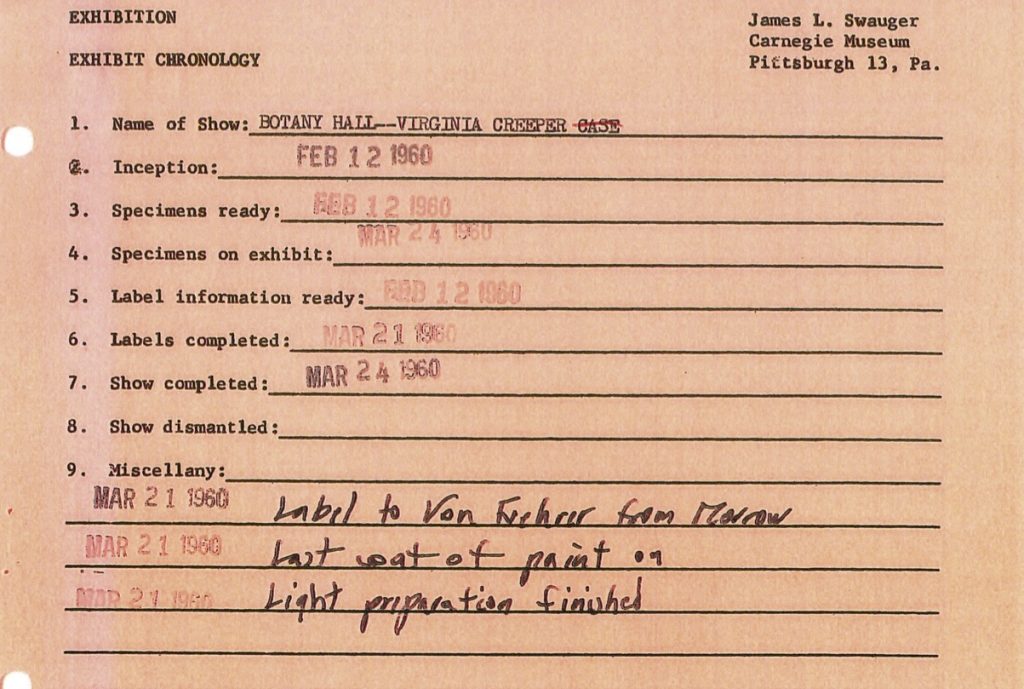

Dioramas are complex objects that are often produced by a team of skilled professionals. Although elements of a diorama may look uncomplicated, they are actually the result of significant observation and collaboration over the course of many months. The “Exhibition Chronology” for one particular component within a diorama may incorporate several phases, from “Inception” through to completion. One such “Chronology,” for Botany Hall’s Virginia Creeper, required eight steps to completion, including label-writing and editing, painting, and light preparation (see image below).[1]

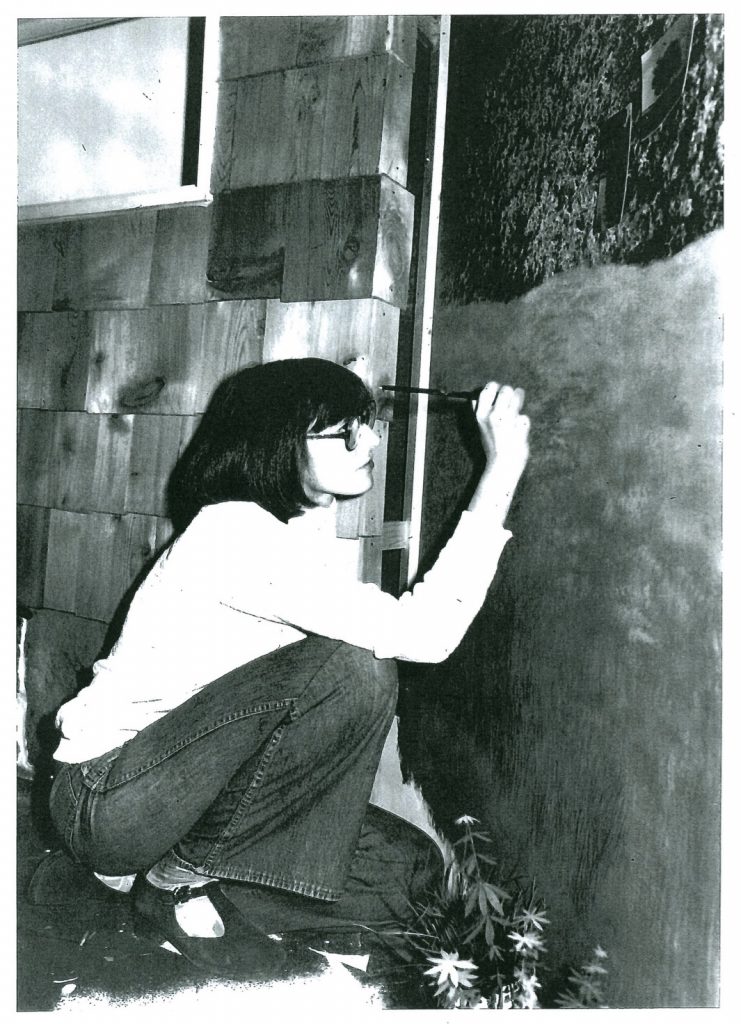

Ottmar von Feuhrer (1900-1967) painted the backgrounds for the botanical dioramas, and for many other dioramas throughout the museum (photo below). Von Fuehrer went on field trips to study the environs he was portraying, including a trip to Florida for the tropical plant group and a trip to Tucson, Arizona for the desert diorama. A letter addressed to Dr. George H. Clapp (then Chairman of the Museum Committee, part of the Board of Trustees at the Carnegie Institute), describes the following:

Mr. Ottmar Fuehrer spent about two weeks at Tucson with our party selecting specimens, making molds, gathering thorns and other accessories, making photographs and packing and shipping the material to the Museum…Mr. Fuehrer made a number of sketches from nature for the background of the group…

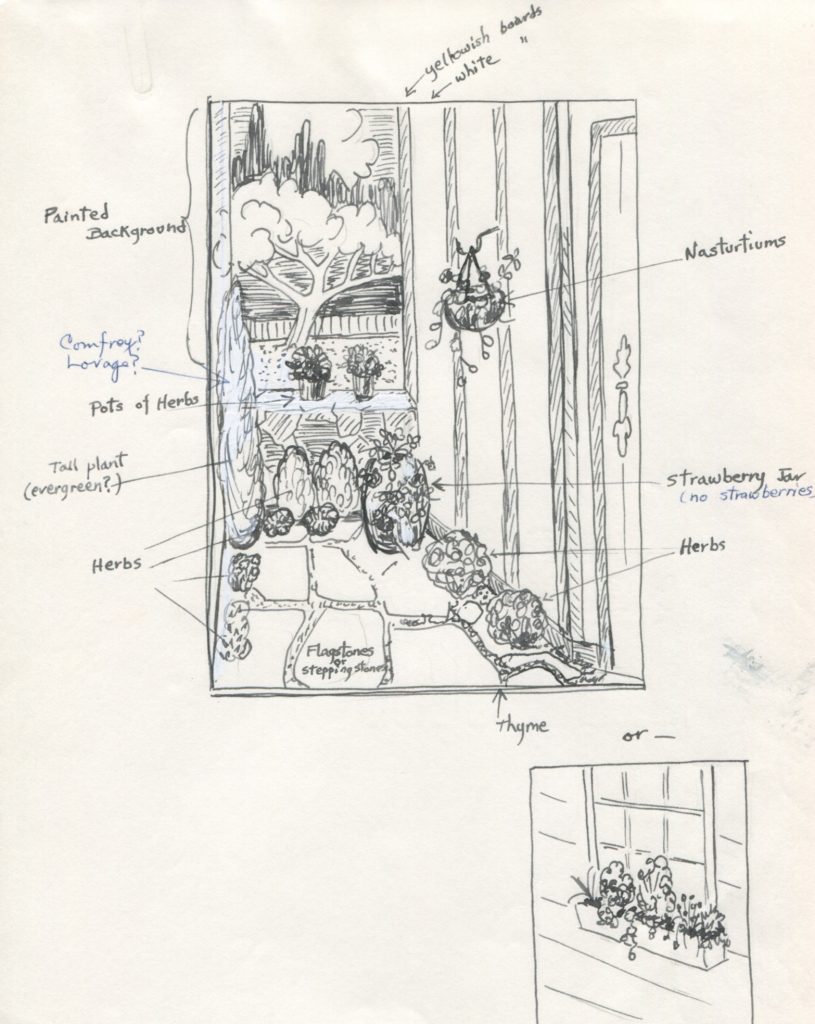

Indeed, scientists, artists, and curators generated ideas for the Botany Hall dioramas during field expeditions. They made observations, collected materials, and created casts and molds on various ventures into the natural world. Specimens collected on such quests were destined for the museum collection, Botany Hall, or sometimes both.

Hanne von Feurher, Ottmar’s wife, along with Carl Beato, and likely Anna Dierdorf, prepared the plants and flowers inside, by hand, using wax and paper. A newspaper article about Dierdorf from this period entitled, “Pittsburgh Woman Chooses Unique Calling And Is the Best in Her Line of Work,” demonstrates the complexity of the plant replication process. “Leaves and flowers are sent back” from expeditions, and then “the dried leaves are moistened and impressions taken of them. Sometimes the leaves are so broken that they have to be patched and put together again before they can be molded.” Further, the article states, “a single leaf will often require as many as seven different colors before it is considered perfect.” The entire process, evidently, was lengthy and sometimes arduous. Tens of thousands of small parts were made for each group.[2]

The number of wax leaves produced for the Florida group totaled 7,000, and the number of flowers exceeded 500. Von Fuehrer was known for her attentiveness to detail. In order to make the leaves of the Florida group look like they’d been ravaged by insects, she lit a match to the wax leaf casts and let the “cotton and wax burn out a little.” [4] The elaborate cases housing these miniature exhibitions were also custom-made: carpenters, in part under the leadership of Wilson Banks, prepared each of the large exhibition cases.

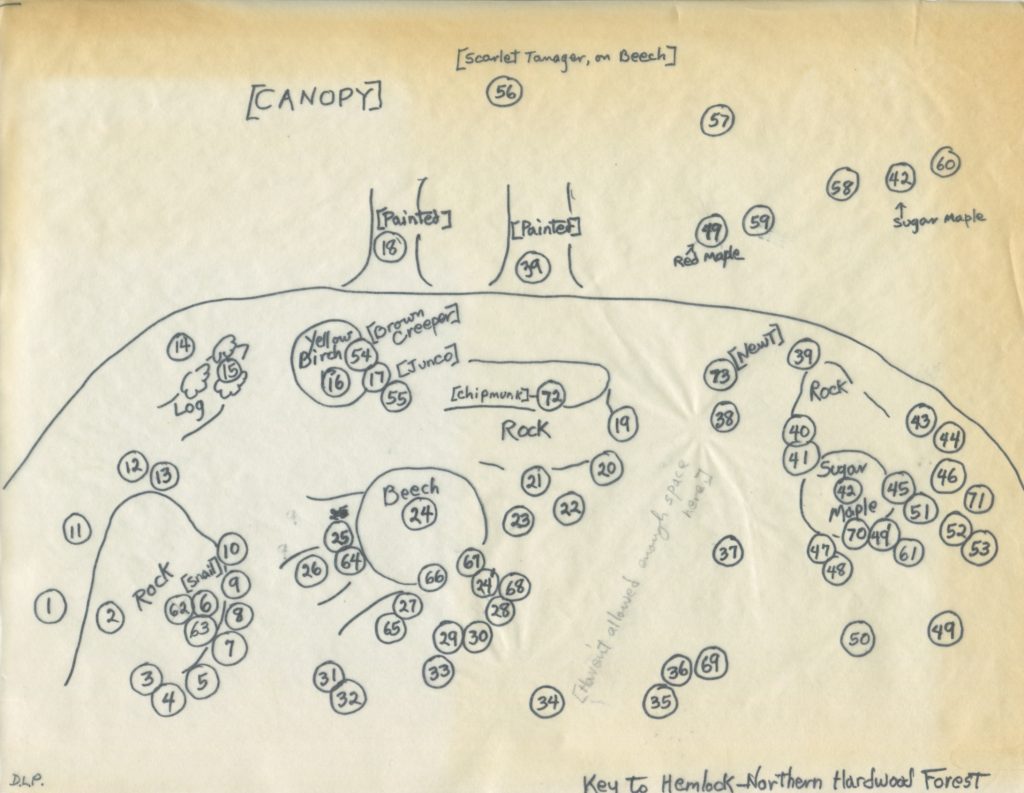

The second round of dioramas required just as many hours of labor. In the publication, Carnegie Museum ’72, the Hardwood Forest is explicated in some detail, revealing multiple layers of production. First, lights and wooden flooring had to be installed, then “an unused steam pipe” removed, walls patched, and “a new frame built to receive the glass front.” In an interview conducted in 1973, Dorothy Pearth alludes to the hybrid nature of this diorama. It is partially man-made and partially “the real thing.” “The leaf litter in the forest is real. The yellow birch trunk is real. The beech is fiber glass, and the the green leaves are plastic.” [3]

In a 1972 letter to the painter Danny Riccobon, Clifford J. Morrow describes a vital stage of the diorama-making process. Morrow writes:

Enclosed you will find a selection of photographs that were taken in northern Pennsylvania. They are scenes of various parts of a hardwood forest. Please use them to develop a painting that will emphasize the hardwoods…

Morrow’s letter reveals the extent to which artists were encouraged to highlight certain aspects of the natural environment, even if it compromised the accuracy of the depiction. The goal was to create the illusion of a unified whole: an immersive sanctuary.

Thus, the final stage of the diorama-making process was particularly crucial. The “tie-in” was the moment when the painter would complete the backdrop in a way that would integrate with the three-dimensional objects.

[1] CMNH Exhibit Section Archive.

[2] Label draft by Pearth in Botany Section, p 42 of Carnegie Museum ‘72, 1973.

[3] P. 12 of ’72; “Museum Unveils Display Of Pennsylvania Forest,” by Woodene Merriman, 1973.

[4] P. 34 Section of Botany CMNH Annual reports.