Viewers

October 4, 2017How have viewers interacted with the dioramas of Botany Hall over the course of its history? In recent decades, natural history museums worldwide have worked hard to maintain the attention of viewers, and to continue to produce productive experiences for them, in an environment when ideas about science, nature, animals, and museum display have shifted and changed in drastic ways.[1] One of the reasons that CMNH’s Botany Hall is so important is that it still exists. Dioramas of this age have been removed from many museum collections, as curators and directors try to address changing times and the ever increasing pressure to fill museums with new technology, rather than technology that is over 100 years old. This section highlights archival remnants of efforts to shape a viewer’s experience in this space, and some notes on the current exhibition design, which prompt reflection on the various ways in which the museum has to continually self-reflect, to ask itself what it is that it wants to do.

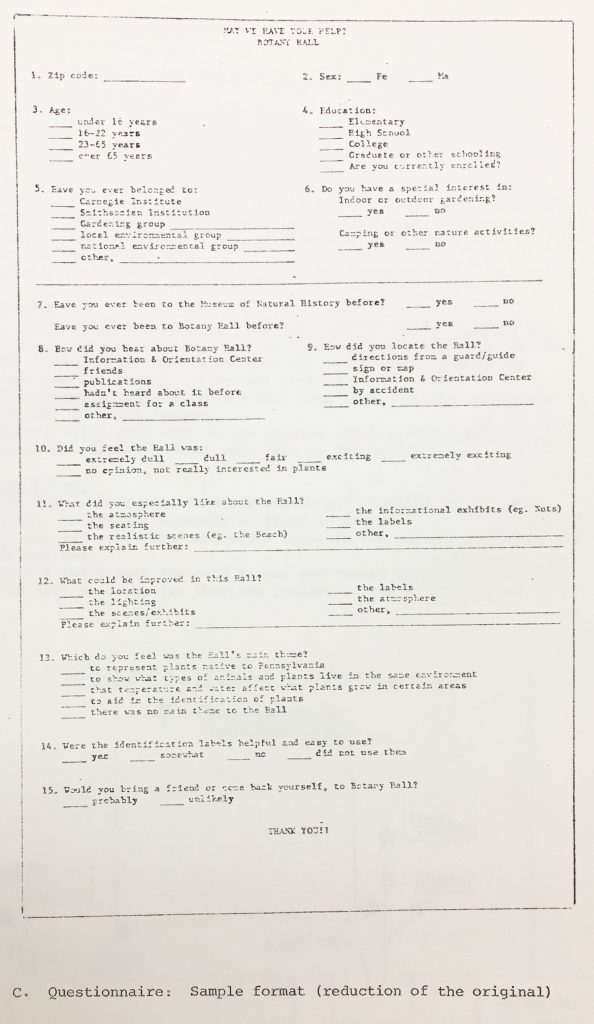

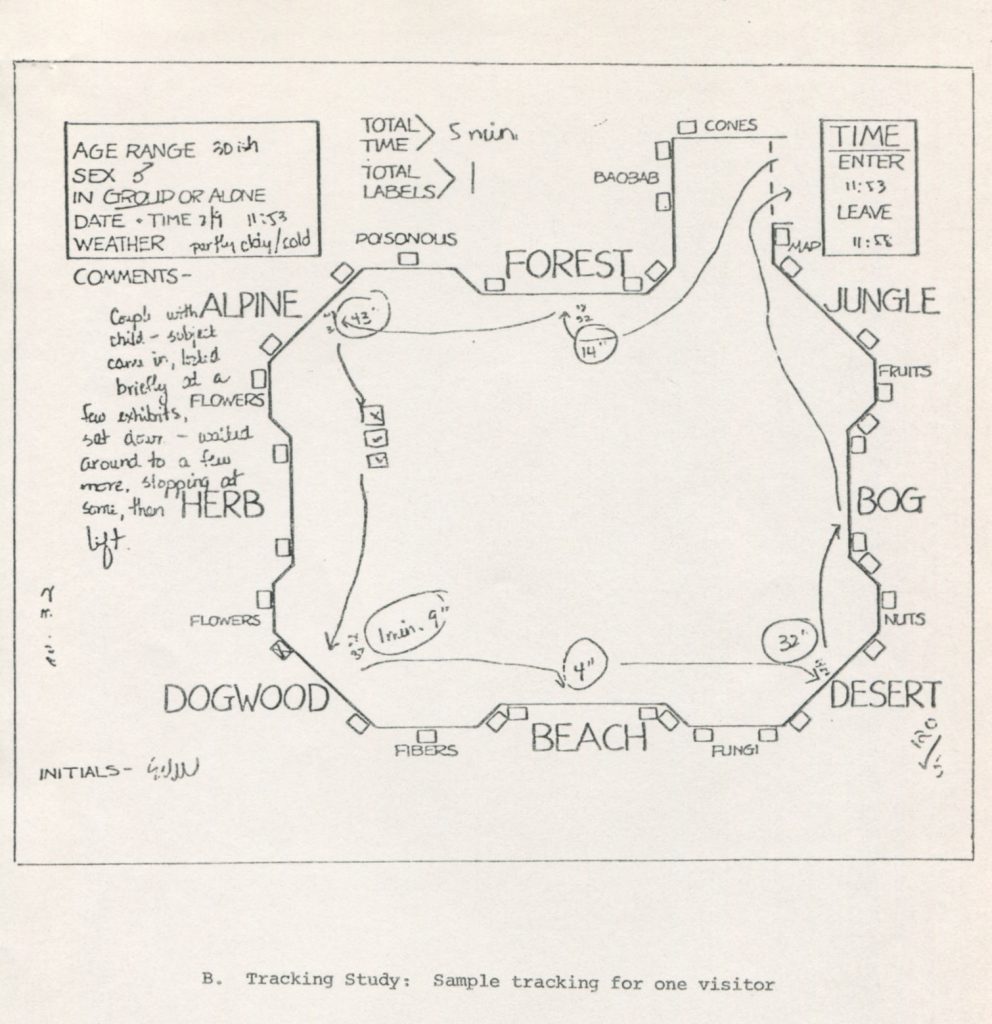

This questionnaire asks if the visitor identified a main theme to the hall (options include how moisture and temperature affect plants, and what combinations of plants and animals live together), if the labels are useful, and if they have a special interest in plants or gardening. The museum was also interested in the flow of a viewer through space, and how much time a person might spend in the hall. This survey affirms an interpretation of the hall’s content that is similar to how it would have been framed in its earliest days. It also shows that museum staff saw the hall as appealing to a special niche audience. Finally, it shows that in the museum framework, Botany Hall asks a lot of its viewers. Comprehending the knowledge above would require more than a stroll through the space, it would require close reading of labels and close looking.

These panels were created in the 1970s and were removed in a renovation in 2013. They were replaced by the panels that are in the hall today. Each has a rather straightforward key, and a viewer is invited to match something they see in the diorama to a number situated in that spot in a photograph, and then find that number in the list below. Because the reference image on the panel is small, the viewer’s attention is directed first to the diorama, then to the label, then back to the diorama. Today’s labels, which include large images of the specimens, invite the viewer to look at the image first, then find the specimen in the diorama.

Also notable is that each label includes the names of the creators of the diorama, in a manner somewhat like a label for an artwork. When the space was renovated, the approach changed slightly. A separate panel was posted, describing the creators in general terms, rather than having each panel include the names. This reflects a late twentieth century shift in many natural history museums, towards an emphasis on framing scientific content independently of an individual creator or a specific technique of craftsmanship. Interestingly, in recent years, there as been a resurgent interest in incorporating these aspects of scientific display into the museum narrative. This is manifested at CMNH in the exhibition, Art of the Diorama, which specifically highlights the artists who worked at the museum. There are also a few out there interested in constructing new dioramas, including the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, although these projects are rare. The Field Museum in Chicago actually crowdsourced funds through the online community of the YouTube channel The Brain Scoop, driven by the work of Emily Graslie, and built a new diorama to house hyenas that had been hunted by famed taxidermist Carl Akeley.

Currently, Botany Hall includes content targeted at children, which is another way in which natural history museums have shifted in the latter half of the twentieth century. During the era of the dioramas’ construction, there is not much in the archive to show that the curators were specifically hoping to appeal to kids, rather that they thought people of all ages could get something out of a visit to the hall. Nowadays, natural history museums work very hard to appeal to families with young children, who are in some cases their main audience.

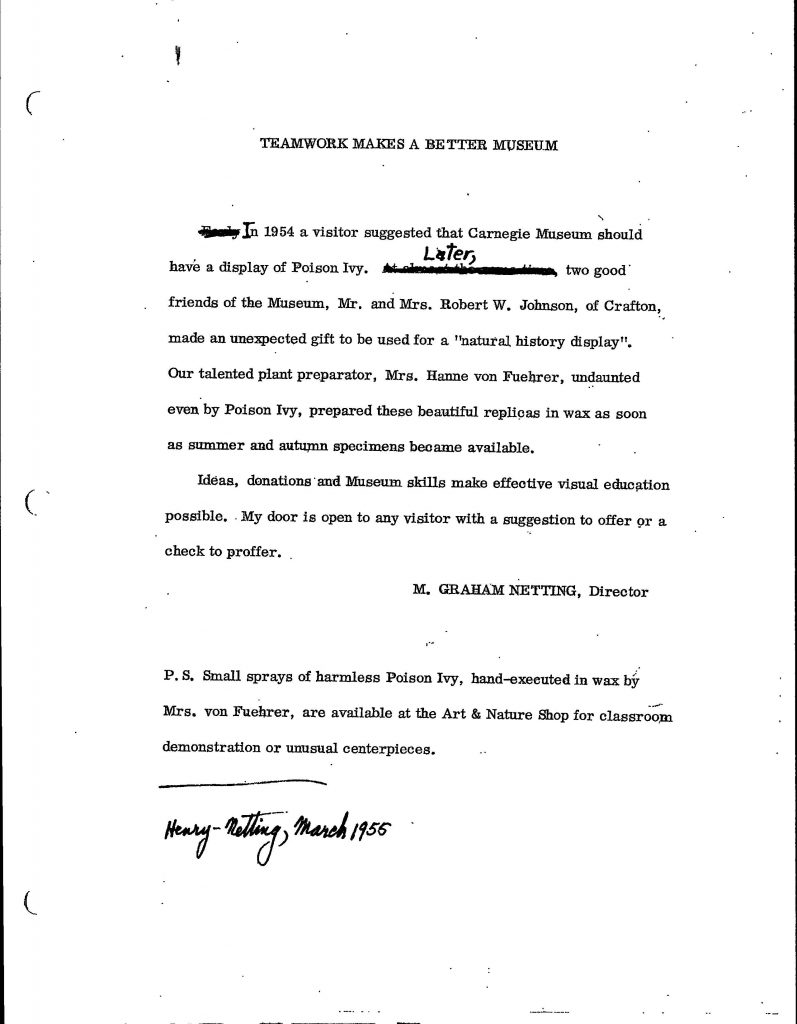

In this label, which may have gone up next to the model of poison ivy, CMNH Director Graham Netting took the opportunity to inform visitors to the hall of the active role they could play in museum display and exhibition design. He writes, “my door is open to any visitor with a suggestion to offer or a check to proffer.” In fact it was true that throughout the history of the hall, dioramas were largely funded by the community, and posting a note like this was a way of making sure the museum didn’t miss out on a potential donor, but may also have had the effect of building on the museum space as a community space at that time.

[1] See Tunnicliffe, Sue Dale, and Annette Scheersoi, eds. Natural History Dioramas. Springer Science + Business Media, Dordrecht, 2015, 1-4.