The Striped Hyena Diorama at the Field Museum

January 10, 2020In July 2018, Aisling and Colleen had the chance to sit down with Emily Graslie, Chief Curiosity Correspondent at the Field Museum in Chicago, and star of the educational YouTube channel, The Brain Scoop. In 2015, Emily ran a crowdfunding campaign via which the international online Brain Scoop community funded the building of a brand new diorama at the Field Museum, a new home for Carl Akeley’s taxidermied striped hyenas and a rare 21st century example of this unique form of scientific visualization. We of course wanted to know more, and so we asked Emily to talk about this whole experience. Our conversation touched on what it was like to combine new techniques with old, what dioramas can do for the public today, the role of technology in science museums, and the challenges of museum education. This transcript of our chat has been edited for clarity.

Colleen: One of the things about dioramas that is most interesting to us and that we’ve been trying to explore in the ones in Pittsburgh is their specific mixture of naturalistic representation and aesthetic strategies. [There are aesthetic] diorama techniques that have been used for so long and are really important to the [science], and in our dioramas at the Carnegie we noticed so many interesting instances where the exhibit designers would make really careful choices that were always about both conveying a certain kind of information and creating a certain visual effect. So we were interested to hear you talk about any aspect of that that happened when you guys were working that was interesting to you or surprised you.

Emily: So my contributions to the project are that Jaap [Hoogstraten, Director of Exhibitions] and I had the idea for it, and we used Brain Scoop as a digital communications platform to raise awareness for it and drive momentum toward it, so really at the front end ideation, fundraising, and the beginning part of the implementation. But I was pretty hands off when it came to the actual craftsmanship of it. So I have a background in art and studio art and large scale landscape painting, but that was really up to their developers and expertise to make those artistic and scientific contributions to it.

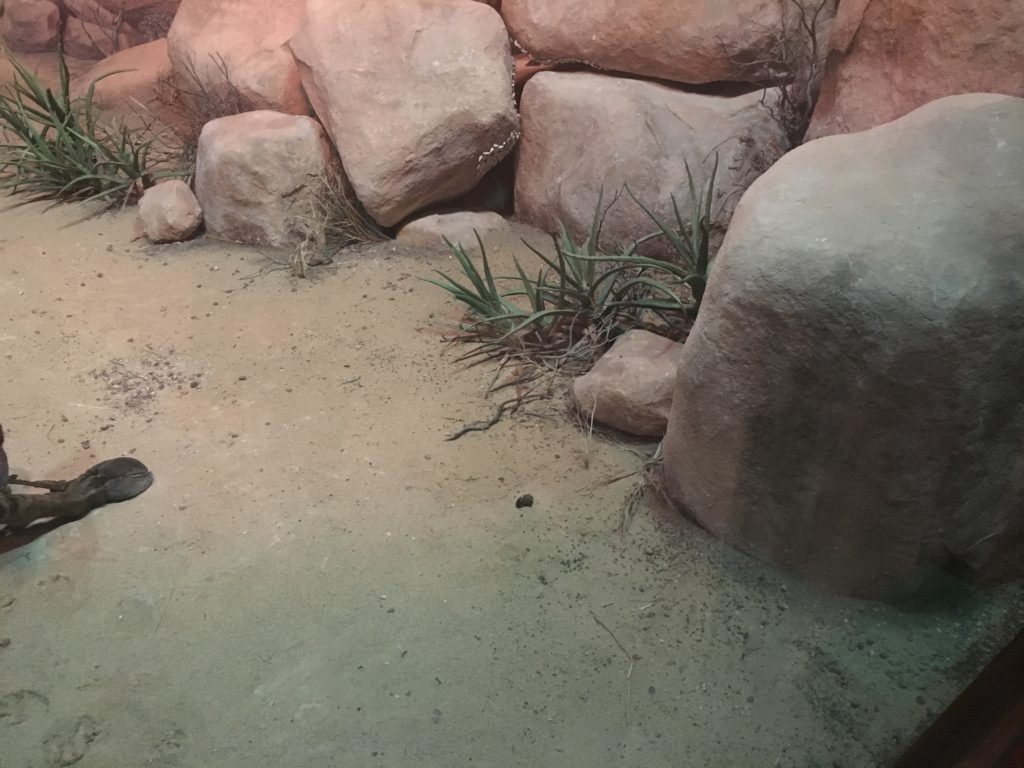

But I can say that what was interesting, from my perspective, is that since it has been so long since we have done something to that scale, it was really a combination of old techniques and new technology. So, for instance, the star patterns in the sky…we were able to figure out what they would be for an exact moment in time and time of day based off this pretty wild software that they use at Adler Planetarium to create sky map projections for a thousand years in the past and a thousand years in the future, so they were able to pinpoint that date in time when the hyenas were collected to figure out where exactly the constellations would be, at what point on the horizon the sun would be coming up at 5:46 in the morning on August 6th, 1896. So from a communications perspective, when I learn that they’re doing that, this combination of really wanting to sort of channel their inner diorama builders from the mid-twentieth century, you know, like, “what would Carl Akeley do? What would Leon Pray think about this fabrication technique?” It was also, at the time it was 2015, so we should be making some conscious decisions to leverage the technologies that we have today that they didn’t have back then in order to convey an extra level of depth of complex information.

So that doesn’t really speak to the artistic choices, but I thought it was pretty interesting how they went to that level of detail across the board. And like I mentioned, the dung beetle ball fabrication, that was another aspect of it that maybe hadn’t been considered before where the exhibitions developers really worked in tandem with the scientific council to make sure they were making things that were as accurate as possible. Just anecdotally, I don’t know that that was how they had approached it previously. I think there was always some input from the mammalogists, but it was to some extent the exhibitions developer was the expert, rather than working with collections folk.

Colleen: The choice of the time of day, to do the morning sunrise sky, was that something to do with the historical situation or was that a choice you guys made?

Emily: It was a choice based off of the life history of the organism. Striped hyenas are nocturnal animals, and they would be most active at night, so I think at the very beginning, when we were still working with Bill Stanley, [the late Director of the Gantz Family Collections Center at the Field Museum] there was some question of like, are we gonna put them in a cave? What time of day is this going to happen? How can we depict that, how do you make a diorama that is supposed to be happening in the dark. So I think that the decision to make it at dawn was sort of a strategic decision to make it so that they would still be active at that time, but maybe sort of wrapping up their evening activities before daybreak, and if you go back and look at it, Aaron Delehanty, who was the artist who painted the background, he had some conversations with an ornithologist in the bird collection to ask him, where would the birds be coming from at this time of day, would they be leaving the roost or coming back to the roost…and so the activity of the organisms in the background is reflective of that too.

Aisling: Did you struggle to articulate the value of creating a new diorama, when you were beginning the promotional process, or when creating the Indiegogo? I’m wondering how you conveyed its importance to a new audience, or to people who are like, “these are old techniques.” We’ve watched your videos but I’m just wondering what those conversations were like.

E: Well it was two separate challenges, one was the internal buy in and one was the external buy in, and I would argue that the internal buy in was harder than the external buy-in. Striped hyenas are not the most charismatic animals for most people. There were a couple people on our development team who were like why can’t you do something like a panda, or a tiger, why these hyenas? It was really a matter of building up that narrative, and it was about looking at someone like Carl Akeley, and not just Carl Akeley but his wife as well. The Akeleys ought to be seen as a package because she was there on this expedition, she was a big contributor to all the techniques, like she did every leaf in the four seasons quadrant of that white-tailed deer diorama, so trying to not leave her out of the narrative. So it was about looking at them from that perspective, about the fact that this was the first American museum-led expedition to Africa ever. The reason for the expedition, was because in part, there was this terrible respiratory disease called the rinderpest virus that had been introduced from Italian livestock, when they came to Ethiopia, and invaded, and there was this civil conflict and colonialism, they brought all their livestock and it infected a lot of the wild livestock. So at the time the Akeleys knew, as well as the mammalogists here at the Field Museum, they knew that the African wild ass was severely endangered. And so they kind of went there with this idea, not to necessarily be conservationists, but they were looking to the future for education. How can we create an environment so future generations can learn and appreciate about these environments, and that might seem a little outdated from our perspective now, but really the narrative is the same. We are still dealing with habitat loss, species decimation, and population decreases. And so, that’s sort of a narrative that has spanned over the last century. As an institution that has invested a lot of money in dioramas over the last hundred years, unless we want our board of trustees’ or the public’s interest to completely die off and to question why we still have these things, then we’ve gotta keep the narrative relevant to today and still impactful. So it was really me working with Jaap, to develop that argument for the value of dioramas, sort of to benefit the rest of the dioramas as a whole, so we had to show we were doing something more contemporary, more relevant, than just replacing glass or just updating reading rails, but actually demonstrating that the public was interested in this, so from that perspective, it was really more about the internal conversation and positioning, than it was getting about getting the buy-in. Because I mean, Brain Scoop has always had a really vocal, niche following, so they want to support any sort of interesting novel project that has anything to do with an interesting and novel area of science, so we were pretty convinced that we’d be able to raise the funds.

C: Was there a part of the conversation where they were like ok we’re sort of interested in this but we need money and then you were like, “what about crowdfunding?”

E: It sort of started with “what about crowdfunding.” I had just started at the museum, so this was like 2013, and it was one of the first conversations I had with Jaap, our Director of Exhibitions, and at that time I was still trying to figure out where Brain Scoop fit in within the organization, right now we really are outreach, science and research, communications, collections, and research, at the time it was like what is the goal of this program, are we trying to drive attendance, are we trying to build enthusiasm for every upcoming exhibition, because we did a lot more about exhibits in the beginning than we do now, sort of because we’ve been able to parse out the value of Brain Scoop, versus what our marketing team is already trying to accomplish. So I went to Jaap with that question, how can we work together, how can we use Brain Scoop to help with your exhibitions, can we get ahead of openings, what can we do. We sat for like an hour and half, and just were kind of spitballing, and nothing really stuck, until, I remember getting up to leave, and being like ok, well, ping me if you think of anything, and he was like well there is this one thing…and that’s when he told me that, it must have been 15 years ago, there was someone who worked in exhibitions who knew about the fact that this diorama space in the Hall of Asian Mammals was boarded up, so that person had planted that seed, about we should do something in that space, and maybe they’d mentioned the hyenas because they were so out of place in the Hall of Reptiles, but maybe it wasn’t the hyenas, maybe it was something else. But at that time, Indiegogo wasn’t a thing, crowdsource funding was not anything that you could even try to do. And so he brought it up and I immediately thought, we should do this with Indiegogo, that would be so amazing. And that’s when we brought the idea to Field Museum development and membership, and it was sort of like well we’ve never done this before, how would we even do this. And I mean, we launched the campaign in 2015, so it took me a year and a half to get internal buy-in and momentum and everything on board, because we had to have a plan B for if we didn’t get the funding, what would we do with it, and we were sort of like, well we can dress up that space, we can replace the glass, we can conserve the specimens, we can build out the landform in their existing habitat a little bit, maybe we won’t do an entire diorama, and we didn’t raise 100% of the money, we raised like 91% which was still enough to do everything we wanted to do, because there was quite a bit of cushion in there. So really it was that I wanted a way to involve my existing digital community in something that was happening here at the Field Museum.

C: It’s fascinating…we’ve come across this too in the culture of natural history museums even across the country, that internally there’s a little bit of angst and stress, about display strategies in general. It’s so smart what you did because I can see how that in doing a new diorama project, it’s not just offering a new diorama project, but you’re actually kind of reframing the whole museum, by delving into this strategy and helping people understand how it works, now the whole collection looks different.

E: Yeah, and not even just our museum, but natural history museums across the board, I mean this is a project I wrapped up in 2015, and two and a half years later, people still want to talk to me about it. I get a lot of feedback from the public, about any diorama thing happening in the news, they make sure I know about it. And I talk to a lot of other museums who are interested in helping to revitalize their spaces too. So I wasn’t insularly thinking about just the Field Museum, but more that this is a service we can do to raise us all up. We all love dioramas, and I would hate for there to be a change in attitude that would have some sort of domino effect, and that was really the concern when the Smithsonian decided to do away with their mammal dioramas, there was really a concern that all mammal displays would go away, that was exacerbated by the Bell Museum deciding to leave and move, and thankfully now they have relocated a lot of theirs and done some conservation work, but I think there was a collective anxiety from people who have worked in and have loved habitat dioramas, that it was beginning of a downward trend, so I saw an opportunity to be like no, not every museum! I’ve heard that with the Smithsonian’s, they needed some work, they had needed some care that hadn’t happened at the time it was needed, and I love their new display so its not to disparage it at all.

C: Is that the one where they have the video…in one of the museums in D.C., some of the taxidermy is contextualized now with video screens in the background?

E: Well the Smithsonian in D.C. had the classic dioramas, and I think some of their spaces were an open environment too, it was just taxidermied animals on platforms…It was pretty traditional, one of our mammal curators here said they were never that great in terms of craftsmanship, I can’t say, maybe they were fine, but about 10 years ago they made the decision to redo their entire mammal hall, and so now when you go, it’s more about comparing and contrasting, at least in the main hall…they were really thinking about every audience when they were building it, and especially, I think, kids, so there are mammals on the ground, mammals up high, they’re kind of all over the place, and some of them are in context with other mammals of their habitat and some of them are juxtaposed by size or shape, but all of their taxidermy, if it’s not historic stuff they restored it was all new, so they’re beautiful mounts, and then they do have some classic dioramas. It looks nice, I’m a fan of what they’ve done, it just isn’t the classic D-shaped diorama.

C: One of the things we wanted to ask you about was what is your wishlist for dioramas in museums around the country, are there other examples of strategies that you think are the way forward or other things you’ve seen that you’re like oh no that’s terrible…

E: There aren’t a lot of broad brushstrokes to be made because every museum is different, and the quality of every museum diorama is different, they can very so dramatically from one to the next, and it depends on a number of factors, from who built it, when it was built, and who has maintained it since then, and also the context that they were created under initially. I think a lot of museums struggle [because] they kind of got on that bandwagon in the early 20th century, let’s make dioramas because we’re all doing it, and then sort of lost their way in terms of, why do we actually have these, especially for environments that aren’t local to the region, I think a lot of smaller museums really benefit from having local habitat dioramas, but I don’t go to the Indiana Dunes to see an African diorama habitat, and I think there’s a little bit of confusion at some places. But I think there are ways of making the conversation contemporary without having to do some temporary skin fixes, which is just like let’s put some audio in here, and let’s change the lighting and put in some new displays, and refresh it. I don’t think that’s how you refresh a space. I think you refresh a space by recontextualizing the dialogue around them. Because the intent that the diorama was created under initially may not not be the reason why it should exist or still exists today. When we were making our Hall of Asian Mammals, hunting was a big deal, trophy hunting was a big deal, these were trophy items, wealthy people wanted to go hunting, they didn’t have room for them in their house, so they donated their panda bears to the Field Museum, so maybe there’s room for a new conversation about how we think about hunting, how hunting can support or doesn’t support conservation, how we talk about habitat loss, because often times, when people walk into a diorama hall, that conversation isn’t happening, there’s no signage around our panda exhibit about anything happening with panda conservation or population numbers or regulation of species, breeding programs, captive breeding programs, nothing, it’s just sort of like here’s a time capsule of a time in the last hundred years, where these animals lived…and if that’s all it is, maybe that’s all it is. But there are just so many more opportunities to keep the conversation going, so that these dioramas don’t become this thing of the past.

A: That’s something we try to contextualize in our website, because Botany Hall was definitely created in part around a conservationist movement, and it’s not clear at all if you’re in there today, but in the past they had juxtaposed one of the dioramas against a miniature version of it with picnic trash in it, and they had that on display for a while, just a very simple way of showing how humans are impacting their environment.

E: I think there’s room for creative things, like having a temporary exhibition where you invite a taxidermist today to make a diorama of landfill, or make a diorama of what that area of Somalia looks like now. The African Striped Hyenas are in the Asian Hall because we wanted to create a dialogue about the historic distribution of that species. They used to be pretty widespread across Africa and parts of Asia, and now they are mostly just in the Middle East, they’re no longer found in that area of Somalia. When we were creating the Brain Scoop videos we talked about that, but I don’t know if that narrative comes across very well in the space they’re in now. I would have to go back and see if its supported in the reading rails. The intent of the dioramas when they were created, because of this idea that kids in and around Chicago, back in the 1920s, likely would never get to go to Central America or Africa or Asia…now everyone has a phone in their pocket, so you’ve gotta re-address that conversation. If you can access information about these animals in any other place except a museum, what purpose are we serving.

C: Which brings in the question again of…I think museums, because of technology, specifically screens, a lot of times that’s where the tension gets centered around, it’s like ok well we have to make these like screens, we have to make them louder and more colorful and they have to be moving, but then I think you’re right, that’s like a left turn in the sense that [dioramas] have a storytelling capability that screens don’t have, that your phone doesn’t have, it’s something so specific that can still be really valuable both in understanding the history of that technique, and in using it today.

E: Yeah, and museums can only do so much with so little time and resources to try and dance the dance or hit the moving target that is public interest and appeal, and at some point society just has to sit down and look at itself and ask what do we really want to get out of our own self-driven education, and it might be a generational thing, like I grew up with a computer, I got internet access when I was ten years old, I have been a child of the internet for the last 20 years of my life, and I’m just now getting to a point where I’m tired of having this thing with me all the time, I’m tired of looking at my phone, I’m tired of the pressure of maintaining a social media presence which is like hustling online, I used to even take my phone with me when I would go running so I could listen to podcasts, and now I just leave it in the car. I just want nothing, I just want nothing more than to be in nature and to enjoy that time, and I think it’s going to really be on the visitor and the culture of museum visitorship, for them to decide what they really want to get out of museums. And that’s why I’m glad that we do have those completely different halls. We’ve got the North American diorama hall where we have tried to hit that moving target, the moving target was moving in the 90s and now it’s stopped and now that hall is the way that it is and it looks dated even though it might have only been 10 years ago that they did those changes, but for the Hall of Asian Mammals, other than the addition of the Striped Hyena diorama and the one reading rail, they haven’t really done much to try and appeal to that. That being said, I don’t know if they’re going to put in more reading rails, and what would that hall look like with another 19 reading rails, or more screens…

A: Yes, that’s why we were resistant to developing a mobile app which was what the museum initially thought we were developing, because we didn’t want to encourage people to be looking at their phones while they were in the Botany Hall space, because we do think that’s the value of museums, being in the presence of physical objects, and it’s all about social engagement with other people, so not saying that I don’t like mobile apps in museums, but I think they can be problematic.

E: Yeah and that’s the push and pull, it’s like we could have not put that reading rail, but then would you know about the implications of the dung beetle, would you know why we decided to make this now after 60 years, there’s the balance between too much information versus not enough context.

A: I think its location is really smart, becauses it’s below the diorama, you’re looking at the diorama and it doesn’t really interfere, there’s a way that they coexist.

E: Yeah it’s not like a television monitor on the wall.

A: Yeah or your phone right next to you, I think that works well actually.

C: We had the same [questions]…we were compelled to make this website, because we felt like maybe this is a way that digital tools can do something that is really difficult in the space of the museum, which is to talk about the history of the objects and the science or their pedagogical function at the same time. But online you can have this flexible thing that people can explore in different ways. So we’re interested in the layers of that conversation here – were there different ideas about how to incorporate digital tools, what those tools should do, even the logistics of who had to kind of work with who to put that together…

E: I wasn’t part of those conversations, but I’ll say from my perspective, there’s very little Brain Scoop stuff in the museum, if you don’t know about me or The Brain Scoop and you come to visit here, you will not learn about our program, so it’s almost the opposite of a museum exhibition, our program exits its chiefly online or through social media, and that’s almost deliberate, we don’t want it to be location specific, we don’t want it to be that you have to come to the Field Museum in order to appreciate the messages and lessons that we’ve tried to communicate through our digital program, we want them to be applicable to museums across the board. And that’s difficult to measure, but anecdotally, if someone’s at a museum in Scotland and they see a picture of a pangolin, they’ll usually send me a picture, so that’s a nice supportive way to help people appreciate museums where they are, but in terms of doing that in the museum, I was not a fly on the wall for those conversations.

C: It sort of sounds like [they should have included you] in some ways, I mean I feel like again there’s just a lot of competing interests and visions for what’s worthwhile for the museum to do…and it’s tricky.

E: Yeah, I mean, the reason why we wanted to do a diorama is because we think that they can transcend time. And if you look at [Brain Scoop’s] viewer demographics, about half of our viewership comes from outside of the United States. So when I was first hired at the museum, there was this real pressure to get like an ROI, like, we’re going to invest money in this program, so you need to demonstrate that you’re driving attendance to the museum. It was kind of hard to do when half of our viewership doesn’t even live in this country. And so we could have made a temporary exhibit, we could have done something that was just about bringing Scoop in, this novel digital project that we have, but instead why don’t we make something permanent that if you watched our show in 2013, and you don’t watch for 10 years, or you contributed to the Indiegogo campaign, then 5, 10, or 50 years later you can come back and see this thing that you contributed to.

A: Yeah, it’s like this intangible impact over time that people are not happy with if they’re in administration and need to track money and stuff…

C: Right..not conducive to the business model…

A: But you’ve increased awareness of the Field Museum around the world in a way that people are citing you when they talk about dioramas in ways that you can’t really grasp if you’re just looking at the numbers.

E: Yeah, and that’s probably my personal problem, maybe I should have been in those conversations, but also I’m just not good at playing the internal politics game. We’re our own department here.

A: Which is probably nice too, like you have more flexibility, probably.

E: We do, and you know very little edit by committee happens when it comes to our program, but the compromise is that were not well integrated into things like the diorama project even, like I mentioned like I had to go to exhibitions and ask that they put up some sort of signage…and like I don’t own The Brain Scoop, it is not mine, it’s a museum program.

C: Yeah, and they should be noticing the ways that that pushes forward their mission that you’ve made very clear, but yeah I can see how…museums are such complex beasts…

E: A lot of competing interests.

C: Yeah, and they are very slow moving, and not that adaptable sometimes, which is again why what you brought in always struck us as so apt, because it is flexible, like the whole structure of crowdfunding and everything, it combined something flexible and adaptable and not tied down…like its global, and it has brought that in contact with what museums do really well which is to make permanent things that are sort of like these sacred spaces.

E: Yeah. It was one of those things where like, I don’t do what I do because I want a temporary fix or some sort of temporary gratification. I don’t aspire to be a viral sensation on YouTube because that’s something that bolsters my self worth or value, like I do what I do because I have a genuine lifelong interest and appreciation for what museums do. So, I’m okay with not having better metrics, like I don’t deliver the impressions of our program to our board every week, I mean we’ve got data and analytics to support the value of what we do and again it’s probably just like my personal problem, or the fact that I’m not good at playing the game but we do it because we do think there’s an intrinsic value that is difficult if not impossible to quantify, so why try to quantify it?

C: I feel like that’s [actually] part of its value that it’s not quantifiable, it doesn’t mesh with, like, corporate growth.

E: It’s the kind of payoff that we might not see for 5 or 20 years, you know? I’ll [have] an email from an eighth-grader five years ago saying I really like bugs, but I’m a girl and I’m not supposed to like bugs, and then five years later I get an email from someone saying that they’re studying entomology at university now, you know? That’s a payoff that I guess I could have marked every time I got a message like that, but why not just let it be what it is.

A: We were wondering if you would take a similar approach if you were to have the opportunity to do a similar kind of project, or if you would ever tackle a similar project? Something that’s within the fabric of the museum that requires crowdfunding.

E: I don’t know, because internally the climate is very different and externally the climate is very different, so there are things that I have completely no control over in terms of like the discoverability of our content on YouTube… so they changed their algorithm in terms of how new content is discoverable by new viewers back in October of last year, and we’ve seen a direct correlation between that and an incredible decrease in our viewership. So it used to be that about 25 to 45 percent of the views on any one of our videos was from subscribers, which means that 75 to 65 percent of the views on something were just from people who saw it come up as a suggested video, what to watch next. Then they made this big change because they wanted to optimize like the existing libraries of educational creators so that videos we’d made in the past would be shown to new people which means that about three of our old videos are now getting a ton of views for no real reason and all of our new videos are getting… like they changed the notifications system so even if you’re subscribed you have to opt in for notifications to get notified for a video and in addition to that because of this algorithm change it’s like 90% of the views on our new videos are just from subscribers, who aren’t getting notified, so viewership on our channel across the board is down, like our latest video has like 20,000 views [and] it used to be between 50 and 60,000 in the first 24 hours of an upload… so like there’s boring stuff like that, and would I do crowdfunding now based off of the lack of discoverability of our content? Probably not, it wouldn’t reach the people who we would intend for it to reach.

But that being said, it was such a project that just made sense for crowdfunding. It was a new, interesting, novel thing for Indiegogo, it’s something that would be really hard to replicate somewhere else, it’s not like we’re, you know, making a novel enamel pin set, or a new kind of sneaker, or a better hydration system, this is a one-and-done, this is a one time special thing. Because that was the question from our development team was, well if this works once, can we do it for all the new exhibits? and it was sort of like, this is just going to be something that we do this one time, and if you participated in it then you got to be part of something really special.